The Science Behind Creative Writing

Amazing new technologies have come along in recent years that enhance or improve almost every job in the advertising field — except writing. So far, no new program, gadget or other modern convenience has come along to help a writer write a great headline, clever copy or improve a bad idea. Since the beginning of advertising, a writer has had to resort to his or her wits, intelligence and reasoning to come up with great ideas and the words to express them.

To compensate for this lack of technological assistance, writers must seek out ways to stimulate our brains and find inspiration in the world as they’ve always done. Some are avid readers; some write on the side in other capacities; some absorb other word-centric arts like comedy, film or even music.

The more we understand the way our brain operates, the better we can connect ideas and come ever closer to the elusive formula for great ideas. Personally, I’m fascinated by the way we think, and obsessed by the various mental phenomena that govern the way we think.

There are number of biases that have sprung up in our brains over our lifetimes, whether we want them to be there or not. Sometimes they stand in our way. They influence our everyday lives without realizing it — as we do our jobs, interact socially, or interpret the world around us. Sometimes, if we’re aware of them, we can learn to circumvent them or even use them to our advantage.

I view these biases, known as cognitive biases, as trees that function as a mental obstacle course that we must navigate to arrive at real truths. There aren’t just a few of them. There are many. A whole forest of them.

What are cognitive biases?

Cognitive biases are tendencies to think in a certain way that can lead to systematic deviations from standard of rationality or good judgment. Some are mental shortcuts we make to produce decisions or judgments. They affect the way we form our beliefs, professional decision-making and human behavior in general. For writers, it’s important that we recognize the existence of these biases, acknowledge them, in order to successfully navigate the creative process.

In the photo above, you can see the light. Or at least sense it. It represents truth, creative epiphany. Pure brilliance. But it’s obscured. I see what looks like a good idea being filtered through these trees, bouncing from one to another before arriving at my brain. But in what form? Without acknowledging the obstacles in our way, this may be as close as we’ll ever get to it.

Let’s go through some cognitive biases that apply to all of us.

Frequency Illusion:

How many times has this happened to you? Frequency Illusion, also known as the Baader-Meinhof Phenomenon, is the illusion in which a word, a name or other thing that has just recently come to your attention suddenly seems to appear with improbable frequency shortly afterwards. For example, I was watching an 80s movie recently in which a character was drinking one of these:

I’d totally forgotten about this brand; it seemed to have vanished from my consciousness. But I moved on. Then the very next day, as if placed there by someone wishing to mess with my head, this popped up in my Facebook newsfeed:

Coincidence? Yes, actually. That’s the Frequency Illusion.

Pareidolia:

A Pareidolia is a somewhat vague and random stimulus upon which we place unfounded significance. This is a fancy way of referring to the bias that makes us hear satanic messages when we play Led Zeppelin backwards, see faces in clouds or Jesus in a tortilla.

Humor Effect:

The Humor Effect states that humorous messaging is more easily remembered than non-humorous messaging. For the sake of argument, let’s pretend that is true. Why do you think that is? This could be explained by the distinctiveness of the humor, like the Old Spice ads of recent years. Maybe it’s the increased cognitive processing time it takes to understand the humor that we find rewarding. Sometimes humor takes a bizarre, subversive approach that begs the audience to ask, “Am I subversive enough to get this and laugh at it?” Whatever the case, humorous messaging often leads to discussion and is perhaps remembered better because we spread the message beyond its original medium.

Rhyme as Reason Effect

The Rhyme as Reason Effect is where rhyming statements are perceived as more effective or truthful. Here’s one of the more famous examples.

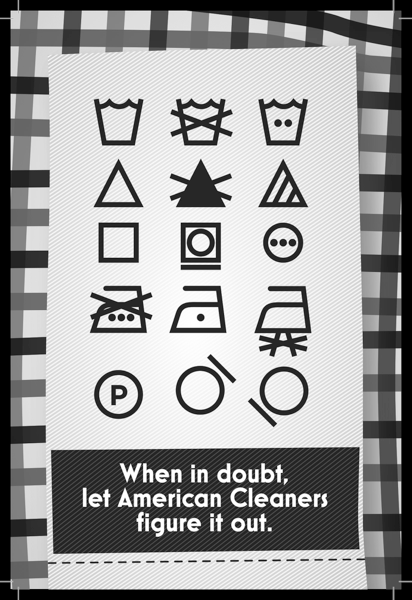

“If it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.” For way too many people, the rhyme was good enough. Regardless, its effectiveness was undeniable. In writing, however, we tend to avoid rhymes as the basis for an idea, but could be used to support a stronger one. For example, this direct mail piece for American Cleaners’ full-service capabilities employs a strong visual gag (playing off those confusing tag symbols), then reinforced by a very-secondary, snappy rhyme.

Continued Influence Effect

This is probably the most obnoxious and troubling bias these days. It’s the tendency to believe previously learned misinformation even after it has been corrected. We see this all the time in politics — where some politician makes a ridiculous claim about something or someone that, through basic research and fact-checking, is proven to be false. And yet, the truth has failed to convince the believers of the lie, and the supports of the liar.

These are just a few of the hundreds, possibly thousands, of cognitive biases that obscure our journey to the truth. Honestly, there’s no way to keep track of them all as we go through life or in the creative process. But if we increase our awareness of them, think about why we think the way we do, that consciousness dissolves the subliminal. And maybe we find ourselves getting closer to purer truths and, thus, better ideas and more effective communications.

(To learn more about VI's Copywriting services, click here)